Highest Note On A Clarinet

B ♭ clarinets (Boehm and Oehler fingering arrangement) | |

| Woodwind instrument | |

|---|---|

| Classification | Single-reed |

| Hornbostel–Sachs nomenclature | 422.211.ii–71 (Single-reeded aerophone with keys) |

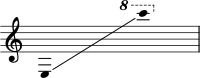

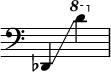

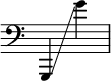

| Playing range | |

| | |

| Related instruments | |

| |

The clarinet is a woodwind musical instrument. The clarinet family is the largest woodwind family, with more than than a dozen types in common use, ranging from the BB♭ contrabass to the E♭ sopranino. The most common clarinet is the B ♭ soprano clarinet. All are single-reed instruments with a nearly-cylindrical bore and a flared bell.

High german instrument maker Johann Christoph Denner is generally credited with inventing the clarinet around the year 1700 by adding a register cardinal to the chalumeau, an before single-reed musical instrument. Over time, additional keywork and the development of closed pads were added to improve the tone and playability.

The clarinet is used in classical music, military bands, klezmer, jazz, and other styles. It is a standard fixture of the orchestra and air current ensemble.

Etymology [edit]

The give-and-take clarinet may have entered the English linguistic communication via the French clarinette (the feminine atomic of Old French clarin), or from Provençal clarin ("oboe").[i] It is ultimately from the Latin root clarus ("articulate").[2] The word is related to Middle English clarion, a type of trumpet, the proper name of which derives from the aforementioned root.[3]

The earliest mention of the discussion clarinette as used for the instrument dates to a 1710 club placed by the Knuckles of Gronsfeld for two of the instrument fabricated past Jacob Denner.[4] [5] The English form clarinet is plant as early equally 1733, and the now-primitive clarionet appears from 1784 until the early years of the 20th century.[half dozen] [7]

A person who plays the clarinet is called a clarinetist (in North American English), a clarinettist (in British English), or simply a clarinet actor.[8]

Characteristics [edit]

The clarinet's cylindrical diameter is the primary reason for its distinctive timbre, which varies betwixt the 3 main registers (the chalumeau, clarion, and altissimo). The A and B ♭ clarinets have nearly the same bore and nearly identical tonal quality, although the A typically has a slightly warmer audio.[nine] The tone of the Eastward ♭ clarinet is brighter and can be heard through loud orchestral textures.[ten] The bass clarinet has a characteristically deep, mellow sound, and the alto clarinet sounds similar to the bass, though non as night.[eleven]

Range [edit]

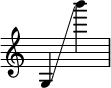

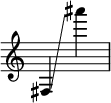

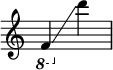

Clarinets take the largest pitch range of common woodwinds.[12] Nearly all soprano and piccolo clarinets have keywork enabling them to play the Due east below eye C equally their everyman written note (in scientific pitch notation that sounds Dthree on a soprano clarinet or C4, i.e. concert middle C, on a piccolo clarinet), though some B ♭ clarinets go down to E ♭ iii to enable them to match the range of the A clarinet.[13] On the B ♭ soprano clarinet, the concert pitch of the everyman note is D3, a whole tone lower than the written pitch.[iv] Many bass clarinets more often than not take boosted keywork to written C3.[xiv] Among the less normally encountered members of the clarinet family unit, contrabass clarinets may have keywork to written D3, C3, or B2;[15] the basset clarinet and basset horn more often than not get to low Ciii.[16] Defining the top finish of a clarinet's range is difficult, since many advanced players can produce notes well to a higher place the highest notes commonly found in method books. G6 is usually the highest annotation encountered in classical repertoire,[17] but fingerings as high as A7 be.[xviii]

The range of a clarinet can be divided into three singled-out registers:

- The lowest register, from low written Eastward to the written B ♭ higher up centre C (B ♭ 4), is known as the chalumeau register[19] (named after the instrument that was the clarinet'south immediate predecessor).[four]

-

- The bridging pharynx tones, from written G to B ♭ , are sometimes treated as a separate annals[four]

- The heart register is known equally the clarion register and spans merely over an octave (from written B above middle C (B4) to the C two octaves above centre C (Cvi)).[19]

- The tiptop or altissimo register consists of the notes above the written C two octaves to a higher place middle C (C6).[19]

All three registers accept characteristically different sounds. The chalumeau annals is rich and dark. The clarion register is brighter and sweet, like a trumpet heard from distant. The altissimo register tin can be piercing and sometimes shrill.[20] [21]

Acoustics [edit]

Sound wave propagation in the soprano clarinet

The production of sound by a clarinet follows these steps:[22] [23] [four]

- The mouthpiece and reed are surrounded past the histrion's lips, which put light, even pressure on the reed and form an closed seal.[24] Air is blown past the reed and down the musical instrument. In the aforementioned way a flag flaps in the breeze, the air rushing past the reed causes it to vibrate. As air pressure from the mouth increases, the amount the reed vibrates increases until the reed hits the mouthpiece.

At this betoken, the reed stays pressed confronting the mouthpiece until either the springiness of the reed forces it to open or a returning pressure moving ridge 'bumps' into the reed and opens it. Each time the reed opens, a puff of air goes through the gap, afterward which the reed swings shut once more. When played loudly, the reed can spend upward to fifty% of the fourth dimension close.[25] The 'puff of air' or pinch wave (effectually 3% greater pressure than the surrounding air[22]) travels down the cylindrical tube and escapes at the betoken where the tube opens out. This is either at the closest open hole or at the end of the tube (see diagram: prototype ane). - More than a 'neutral' corporeality of air escapes from the instrument, which creates a slight vacuum or rarefaction in the clarinet tube. This rarefaction wave travels dorsum up the tube (paradigm 2).

- The rarefaction is reflected off the sloping terminate wall of the clarinet mouthpiece. The opening between the reed and the mouthpiece makes very little deviation to the reflection of the rarefaction wave. This is because the opening is very minor compared to the size of the tube, so almost the entire wave is reflected back down the tube even if the reed is completely open at the fourth dimension the moving ridge hits (prototype 3).

- When the rarefaction wave reaches the other (open) end of the tube, air rushes in to fill the slight vacuum. A little more than a 'neutral' amount of air enters the tube and causes a pinch wave to travel back up the tube (image 4). In one case the pinch wave reaches the mouthpiece end of the 'tube', it is reflected again back down the pipe. However at this point, either because the compression wave 'bumped' the reed or considering of the natural vibration cycle of the reed, the gap opens and another 'puff' of air is sent down the pipe.

- The original compression moving ridge, now greatly reinforced past the 2nd 'puff' of air, sets off on another two trips downwardly the pipe (travelling 4 pipe lengths in total) before the wheel is repeated once more.[22]

In addition to this main compression wave, other waves, known as harmonics, are created. Harmonics are caused by factors including the imperfect wobbling and shaking of the reed, the reed sealing the mouthpiece opening for office of the wave cycle (which creates a flattened section of the sound wave), and imperfections (bumps and holes) in the bore. A wide diversity of compression waves are created, only merely some (primarily the odd harmonics) are reinforced.[26] [4] This in combination with the cutting-off frequency (where a significant drop in resonance occurs) results in the characteristic tone of the clarinet.[4]

The bore is cylindrical for nigh of the tube with an inner diameter bore between 0.575 and 0.585 millimetres (0.0226 and 0.0230 in), just at that place is a subtle hourglass shape, with the thinnest part below the junction between the upper and lower joint.[27] This hourglass shape, although invisible to the naked eye, helps to correct the pitch and responsiveness of the instrument.[27] The bore of the bore affects the instrument's sound characteristics.[4] The bong at the bottom of the clarinet flares out to amend the tone and tuning of the lowest notes.[22] The fixed reed and fairly compatible diameter of the clarinet requite the instrument an acoustical beliefs approximating that of a cylindrical stopped piping.[22] Recorders use a tapered internal bore to overblow at the octave when the pollex/register hole is pinched open up, while the clarinet, with its cylindrical bore, overblows at the twelfth.[22]

Most modern clarinets take "undercut" tone holes that improve intonation and sound. Undercutting means chamfering the bottom edge of tone holes inside the bore. Acoustically, this makes the tone hole part as if it were larger, but its main function is to allow the air cavalcade to follow the curve up through the tone pigsty (surface tension) instead of "blowing past" it under the increasingly directional frequencies of the upper registers.[28] Covering or uncovering the tone holes varies the length of the pipe, irresolute the resonant frequencies of the enclosed air column and hence the pitch. The histrion moves between the chalumeau and clarion registers through use of the register key; the alter from chalumeau annals to clarion register is termed "the suspension". The open register key stops the central frequency from being reinforced, and the reed is forced to vibrate at three times the speed information technology was originally. This produces a note a twelfth above the original note.[22]

Most woodwind instruments have a second register that begins an octave in a higher place the first (with notes at twice the frequency of the lower notes). With the aid of an 'octave' or 'register' primal, the notes audio an octave higher as the fingering pattern repeats. These instruments are said to overblow at the octave. The clarinet differs, since it acts as a closed-pipe system. The low chalumeau annals plays fundamentals, but the clarion (second) register plays the third harmonics, a perfect twelfth higher than the fundamentals. The clarinet is therefore said to overblow at the 12th.[22] [23] The showtime several notes of the altissimo (3rd) range, aided by the register key and venting with the first left-paw hole, play the fifth harmonics, a perfect 12th plus a major 6th above the fundamentals.[22] [iv] The fifth and seventh harmonics are also available, sounding a further sixth and fourth (a apartment, diminished fifth) higher respectively; these are the notes of the altissimo register.[22]

The lip position and pressure, shaping of the vocal tract, choice of reed and mouthpiece, amount of air pressure created, and evenness of the airflow account for most of the player's ability to control the tone of a clarinet.[29] Their vocal tract volition be shaped to resonate at frequencies associated with the tone being produced.[xxx] Vibrato, a pulsating change of pitch, is rare in classical literature; however, certain performers, such equally Richard Stoltzman, utilise vibrato in classical music.[31] Special fingerings and lip-angle may be used to play microtonal intervals.[32] At that place have also been efforts to create a quarter tone clarinet.[33] [34]

Fritz Schüller's quarter-tone clarinet

Structure [edit]

Materials [edit]

Clarinet bodies have been made from a variety of materials including wood, plastic, hard rubber or Ebonite, metal, and ivory.[35] The vast bulk of wooden clarinets are made from blackwood, grenadilla, or, more uncommonly, Honduran rosewood or cocobolo.[36] [37] Historically other wood, especially boxwood and ebony, were used.[36] Nigh student clarinets are made of plastic, such every bit ABS.[38] [39] One such blend of plastic is Resonite, a term originally by trademarked by Selmer.[xl] [41] The Greenline model by Cafe Crampon is made from a composite of resin and the African blackwood powder left over from the industry of wooden clarinets.[42] [43]

Metal soprano clarinets were popular in the late 19th century, particularly for war machine use, and metallic construction is still used for the bodies of some contra-alto and contrabass clarinets and the necks and bells of most all alto and larger clarinets.[44] [45]

Mouthpieces are more often than not fabricated of hard condom, although some cheap mouthpieces may be made of plastic. Other materials such as glass, wood, ivory, and metal have also been used.[46] Ligatures are often made of metal and tightened using one or more than adjustment screws; other materials include plastic or cord, or fabric.[47]

Reed [edit]

The clarinet uses a single reed made from the cane of Arundo donax.[48] [49] Reeds may also be manufactured from synthetic materials.[l] The ligature fastens the reed to the mouthpiece. When air is blown through the opening between the reed and the mouthpiece facing, the reed vibrates and produces the clarinet's sound.[51]

Well-nigh players buy manufactured reeds, although many make adjustments to these reeds, and some make their own reeds from cane "blanks".[52] Reeds come in varying degrees of hardness, generally indicated on a scale from one (soft) through five (difficult). This numbering system is not standardized—reeds with the same number often vary in hardness across manufacturers and models. Reed and mouthpiece characteristics work together to determine ease of playability and tonal characteristics.[53]

Components [edit]

Mouthpiece with conical ring ligature, fabricated from hard prophylactic

The reed is attached to the mouthpiece by the ligature, and the acme half-inch or and then of this assembly is held in the player's mouth. In the past, cord was used to bind the reed to the mouthpiece. The formation of the oral cavity around the mouthpiece and reed is called the embouchure. The reed is on the underside of the mouthpiece, pressing against the player's lower lip, while the top teeth normally contact the top of the mouthpiece (some players roll the upper lip under the top teeth to form what is chosen a 'double-lip' embouchure).[54] Adjustments in the strength and shape of the embouchure change the tone and intonation (tuning). It is non uncommon for players to employ methods to salvage the pressure on the upper teeth and inner lower lip by attaching pads to the top of the mouthpiece or putting (temporary) padding on the front lower teeth, usually from folded paper.[55]

Next is the curt barrel; this part of the instrument may be extended to fine-tune the clarinet. Interchangeable barrels whose lengths vary slightly tin be used to adjust tuning. Additional bounty for pitch variation and tuning can be made by pulling out the barrel and thus increasing the musical instrument's length.[four] [56] On basset horns and lower clarinets, the barrel is unremarkably replaced by a curved metal neck.[57]

The main body of about clarinets is divided into the upper joint, the holes and most keys of which are operated past the left hand, and the lower joint with holes and about keys operated by the right mitt.[4] Some clarinets have a single articulation.[iv] The body of a modern soprano clarinet is equipped with numerous tone holes of which seven are covered with the fingertips, and the rest are opened or closed using a prepare of 17 keys.[4] The virtually mutual organization of keys was named the Boehm system by its designer Hyacinthe Klosé in accolade of flute designer Theobald Boehm, merely it is not the same as the Boehm organisation used on flutes.[58] The other main system of keys is chosen the Oehler organisation and is used mostly in Germany and Austria.[sixteen] The related Albert organization is used past some jazz, klezmer, and eastern European folk musicians.[sixteen] The Albert and Oehler systems are both based on the early Mueller system.[16]

The cluster of keys at the lesser of the upper articulation (protruding slightly beyond the cork of the articulation) are known equally the trill keys and are operated by the right hand.[59] The entire weight of the smaller clarinets is supported by the right thumb backside the lower articulation on what is called the pollex-residuum.[threescore] Larger clarinets are supported with a neck strap or a floor peg.[61]

Finally, the flared terminate is known equally the bell. Contrary to popular belief, the bell does not amplify the sound; rather, it improves the uniformity of the instrument'southward tone for the lowest notes in each annals.[22] For the other notes, the sound is produced near entirely at the tone holes, and the bell is irrelevant.[22] On basset horns and larger clarinets, the bell curves upwardly and forward and is usually made of metal.[57]

History [edit]

The clarinet has its roots in the early on single-reed instruments used in Ancient Hellenic republic and Ancient Egypt.[62] The mod clarinet adult from a Baroque musical instrument called the chalumeau. This musical instrument was similar to a recorder, simply with a unmarried-reed mouthpiece and a cylindrical diameter. Defective a register primal, information technology was played mainly in its fundamental register, with a express range of about 1 and a half octaves. Information technology had eight finger holes, like a recorder, and ii keys for its two highest notes. At this time, contrary to modern practise, the reed was placed in contact with the upper lip.[63]

Around the turn of the 18th century, the chalumeau was modified past converting 1 of its keys into a register fundamental to produce the first clarinet. This evolution is unremarkably attributed to German language musical instrument maker Johann Christoph Denner, though some have suggested his son Jacob Denner was the inventor.[64] [65] Early clarinets did not play well in the lower register, so players connected to play the chalumeau for low notes.[63] [66] As clarinets improved, the chalumeau savage into decay, and these notes became known as the chalumeau register. Original Denner clarinets had 2 keys, and could play a chromatic scale, simply diverse makers added more keys to get improved tuning, easier fingerings, and a slightly larger range.[63] The clarinet of the Classical menstruation, as used by Mozart, typically had five keys.[16]

Clarinets were before long accustomed into orchestras. Later on models had a mellower tone than the originals. An early champion of the instrument was Mozart, who considered its tone the closest in quality to the human voice and wrote numerous pieces for the instrument.[67] By the time of Beethoven (c. 1780–1820), the clarinet was a standard fixture in the orchestra.[68]

The next major development in the history of clarinet was the invention of the mod pad.[69] Considering early clarinets used felt pads to encompass the tone holes, they leaked air. This required pad-covered holes to be kept to a minimum, restricting the number of notes the clarinet could play with good tone.[69] In 1812, Iwan Müller adult a new type of pad that was covered in leather or fish bladder.[33] It was airtight and let makers increase the number of pad-covered holes. Müller designed a new type of clarinet with seven finger holes and xiii keys.[33] He referred to this model every bit "omnitonic" since it was capable of playing in all keys, rather than requiring alternating joints as was mutual at the time.[16]

Keywork and toneholes [edit]

The final development in the modernistic pattern of the clarinet used in well-nigh of the globe today was introduced by Hyacinthe Klosé in 1839.[58] He implemented ring keys that eliminated the need for complicated fingering patterns.[4] It was inspired by the Boehm system developed for flutes past Theobald Boehm. Klosé was so impressed by Boehm'south invention that he named his own system for clarinets the Boehm system, although it is unlike from the one used on flutes.[58] This new organisation was irksome to gain popularity but gradually became the standard, and today the Boehm system is used everywhere in the world except Deutschland and Austria. These countries all the same use a straight descendant of the Mueller clarinet known as the Oehler system clarinet.[70] Some contemporary Dixieland players continue to use Albert system clarinets.[16] [71]

Other key systems have been adult, many congenital around modifications to the basic Boehm system, including the Total Boehm, Mazzeo, McIntyre,[72] Benade NX,[73] and the Reform Boehm system.[74]

- Clarinets with different arrangements of keys and holes

Early Clarinet with iv keys (ca. 1760).

Iwan Müller clarinet with 13 keys and leather pads, adult in 1809.

Albert clarinet designed ca. 1850 by Eugène Albert, intermediate between the Müller and Oehler clarinets.

Baermann clarinet, ca. 1870, intermediate between the Müller and Oehler clarinets.

Oehler clarinet with a comprehend on the centre tone pigsty of the lower joint and a bell mechanism to amend low E and F. Developed in 1905 by Oscar Oehler.

Standard German clarinet without comprehend or bell machinery.

French Clarinet (Original Boehm with 17 keys and half-dozen rings). Developed ca. 1843 by Hyacinthe Klosé and Louis Auguste Buffet.

Total Boehm clarinet with xix keys and vii rings developed ca. 1870.

Reform Boehm clarinet with 20 keys and 7 rings, developed ca. 1949 past Fritz Wurlitzer.

Usage and repertoire [edit]

Use of multiple clarinets [edit]

The modern orchestral standard of using soprano clarinets in B ♭ and A has to do partly with the history of the instrument and partly with acoustics, aesthetics, and economics. Before near 1800, due to the lack of airtight pads, practical woodwinds could have only a few keys to control accidentals (notes outside their diatonic dwelling house scales).[69] The depression (chalumeau) annals of the clarinet spans a twelfth (an octave plus a perfect fifth), so the clarinet needs keys/holes to produce all nineteen notes in this range. This involves more keywork than on instruments that "overblow" at the octave—oboes, flutes, bassoons, and saxophones, for case, which demand only twelve notes before overblowing. Clarinets with few keys cannot therefore easily play chromatically, limiting whatsoever such instrument to a few closely related keys.[75] For example, an eighteenth-century clarinet in C could be played in F, C, and Grand (and their relative minors) with good intonation, just with progressive difficulty and poorer intonation as the key moved away from this range.[75] With the invention of the closed pad, and equally key technology improved and more keys were added to woodwinds, the need for clarinets in multiple keys was reduced.[sixteen] However, the utilise of multiple instruments in different keys persisted, with the 3 instruments in C, B ♭ , and A all used as specified by the composer.[76]

The lower-pitched clarinets audio "mellower" (less bright), and the C clarinet—being the highest and therefore brightest of the three—savage out of favor as the other two could cover its range and their audio was considered better.[75] While the clarinet in C began to fall out of general use effectually 1850, some composers connected to write C parts afterward this date, e.thou., Bizet'due south Symphony in C (1855), Tchaikovsky's Symphony No. 2 (1872), Smetana's overture to The Bartered Bride (1866) and Má Vlast (1874), Dvořák's Slavonic Dance Op. 46, No. 1 (1878), Brahms' Symphony No. 4 (1885), Mahler's Symphony No. 6 (1906), and Strauss' Der Rosenkavalier (1911).[76]

While technical improvements and an equal-tempered scale reduced the need for ii clarinets, the technical difficulty of playing in remote keys persisted, and the A has thus remained a standard orchestral instrument. In addition, by the tardily 19th century, the orchestral clarinet repertoire contained so much music for clarinet in A that the disuse of this instrument was non applied.[16]

Classical music [edit]

The orchestra frequently includes 2 players on private parts—each histrion is usually equipped with a pair of standard clarinets in B ♭ and A, and clarinet parts unremarkably alternate between the instruments.[77] In the 20th century, composers such as Igor Stravinsky, Richard Strauss, and Gustav Mahler employed many different clarinets including the E ♭ or D soprano clarinets, basset horn, bass clarinet, and/or contrabass clarinet. The exercise of using a variety of clarinets to achieve coloristic variety was common in 20th-century classical music.[78] [79] [77]

In a concert ring or wind ensemble, clarinets are an of import office of the instrumentation. The Eastward ♭ clarinet, B ♭ clarinet, alto clarinet, bass clarinet, and contra-alto/contrabass clarinet are commonly used in concert bands, which mostly have multiple B ♭ clarinets; in that location are commonly three or fifty-fifty four B ♭ clarinet parts with 2–3 players per part.[eighty]

The clarinet is widely used as a solo instrument. The relatively late evolution of the clarinet (when compared to other orchestral woodwinds) has left solo repertoire from the Classical period and later, only few works from the Baroque era. Many clarinet concertos and clarinet sonatas have been written to showcase the musical instrument, for example those by Mozart and Weber.[81]

Many works of sleeping room music accept as well been written for the clarinet. Mutual combinations are:

- Clarinet and piano[82]

- Clarinet trio: clarinet, piano, and some other instrument (for example, a cord instrument)[81]

- Clarinet quartet: iii B ♭ clarinets and bass clarinet; two B ♭ clarinets, alto clarinet, and bass; and other possibilities such equally the apply of a basset horn, especially in European classical works.[83] [57]

- Clarinet quintet: a clarinet plus a cord quartet or, in more than contemporary music, a configuration of five clarinets.[84] [8]

- Air current quintet: flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, and horn.[85]

Groups of clarinets playing together have become increasingly popular amongst clarinet enthusiasts in recent years. Mutual forms are:

- Clarinet choir: which features a large number of clarinets playing together, unremarkably involves a range of unlike members of the clarinet family. The homogeneity of tone across the different members of the clarinet family produces an issue with some similarities to a human choir.[86]

- Clarinet quartet: usually three B ♭ sopranos and one B ♭ bass, or two B ♭ , an E ♭ alto clarinet, and a B ♭ bass clarinet, or sometimes iv B ♭ sopranos.[87]

Jazz [edit]

The clarinet was originally a central musical instrument in jazz, beginning with the Dixieland players in the 1910s. It remained a signature instrument of jazz music through much of the big band era into the 1940s. American players Alphonse Picou, Larry Shields, Jimmie Noone, Johnny Dodds, and Sidney Bechet were all prominent early jazz clarinetists.[71] Swing performers such as Benny Goodman and Artie Shaw rose to prominence in the tardily 1930s.[71]

Beginning in the 1940s, the clarinet faded from its prominent position in jazz.[88] [71] Past that time, an involvement in Dixieland or traditional New Orleans jazz had revived; Pete Fountain was one of the best known performers in this genre.[88] [89] The clarinet'due south place in the jazz ensemble was usurped by the saxophone, which projects a more powerful audio and uses a less complicated fingering system.[90] However, the clarinet did non entirely disappear from jazz. Prominent players since the 1950s include Stan Hasselgård, Jimmy Giuffre, Eric Dolphy (on bass clarinet), Perry Robinson, and John Carter. In the US, the prominent players on the instrument since the 1980s have included Eddie Daniels, Don Byron, Marty Ehrlich, Ken Peplowski, and others playing the clarinet in more gimmicky contexts.[71]

Other genres [edit]

The clarinet is uncommon, merely not unheard of, in stone music. Jerry Martini played clarinet on Sly and the Family Stone'southward 1968 striking, "Dance to the Music".[91] The Beatles included a trio of clarinets in "When I'm Lx-Four" from their Sgt. Pepper'due south Lonely Hearts Club Band album.[92] A clarinet is prominently featured for what a Billboard reviewer termed a "Benny Goodman-flavored clarinet solo" in "Breakfast in America", the championship vocal from the Supertramp album of the same proper name.[93]

Clarinets feature prominently in klezmer music, which entails a distinctive style of playing.[94] The use of quarter-tones requires a dissimilar embouchure.[32]

The pop Brazilian music style of choro uses the clarinet,[95] as do Albanian saze and Greek koumpaneia folk ensembles,[96] Bulgarian hymeneals music,[97] and Turkish folk music.[98]

Clarinet family [edit]

Contrabass and contra-alto clarinets

| Name | Fundamental | Commentary | Range (sounding) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A ♭ clarinet (Piccolo clarinet in A ♭ ) | A ♭ | Now rare, although it was once frequency used in wind ensembles specially in Espana and Italian republic.[78] | |

| E ♭ clarinet (Sopranino or piccolo clarinet in Due east ♭ ) | E ♭ | Information technology has a characteristically "hard and bitter" tone and is used to peachy effect in the classical orchestra whenever a brighter, or sometimes more comical, sound is called for.[78] | |

| D clarinet (Sopranino or piccolo clarinet in D) | D | This instrument was largely replaced past the F and later the East ♭ . Though a few early pieces were written for information technology, its repertoire is now very limited in Western music. Still, Stravinsky included both the D and Eastward ♭ clarinets in his instrumentation for The Rite of Bound.[78] | |

| C clarinet (Soprano clarinet in C) | C | Although this clarinet was very common in the instrument'southward primeval menstruum, its utilise began to dwindle, and past the second decade of the twentieth century, it had become practically obsolete and disappeared from the orchestra. From the time of Mozart, many composers began to favor the mellower, lower-pitched instruments, and the timbre of the C instrument may have been considered too bright.[76] Also, to avert having to carry an extra musical instrument that required another reed and mouthpiece, orchestral players preferred to play parts for this musical instrument on their B ♭ clarinets, transposing up a tone.[99] | |

| B ♭ clarinet (Soprano clarinet in B ♭ ) | B♭ | The near common type of clarinet[77] and used in nigh styles of music. Information technology was normally used in early on jazz and swing.[71] Usually, the generic term "clarinet" on its own refers to this instrument.[100] | |

| A clarinet (Soprano clarinet in A) | A | It is often used in orchestral and chamber music, especially of the nineteenth century.[four] | |

| Basset clarinet | A | Clarinet in A extended to a low C; used primarily to play Classical-era music.[xvi] Mozart's Clarinet Concerto was written for this musical instrument. Basset clarinets in C and B ♭ besides exist.[101] | |

| Basset horn | F | Similar in appearance to the alto, but differs in that it is pitched in F and has a narrower bore on most models. Mozart's Clarinet Concerto was originally sketched out as a concerto for basset horn in One thousand. Little material for this instrument has been published.[57] | |

| Alto clarinet | Eastward ♭ | Sometimes referred to as the tenor clarinet in Europe, it is used in military and concert bands, and occasionally, if rarely, in orchestras.[102] [103] [104] The alto clarinet in F was used in armed forces bands during the early 19th century and was a choice instrument of Iwan Müller. However, it fell out of use, and if chosen for, is commonly substituted with the basset horn.[105] | |

| Bass clarinet | B ♭ | Adult in the belatedly 18th century, it began featuring in orchestral music in the 1830s after its redesign past Adolphe Sax.[106] Since and then, it has become a mainstay of the modern orchestra.[79] It is used in concert bands and enjoys, along with the B ♭ clarinet, a considerable office in jazz, particularly through jazz musician Eric Dolphy.[80] [71] The bass clarinet in A, which had a faddy amongst certain composers from the mid-19th to the mid-20th centuries, is at present so rare as to unremarkably be considered obsolete.[103] | |

| E ♭ contrabass clarinet (likewise called Contra-alto or Contralto clarinet) | EE ♭ | Used in wind ensembles and occasionally for cinematic scores.[79] | |

| Contrabass clarinet (also called double-bass clarinet) | BB ♭ | Used in clarinet ensembles, concert bands, and sometimes in orchestras.[79] Arnold Schoenberg calls for a contrabass clarinet in A in his Five Pieces for Orchestra, only no such instrument always existed.[107] [108] | |

| Subcontrabass clarinet (besides called octocontralto clarinet clarinet or octocontrabass clarinet) | EEE ♭ or BBB ♭ | A largely experimental instrument with little repertoire. Three versions in EEE♭ (an octave below the contra-alto clarinet) were made, and a version in BBB ♭ (an octave below the contrabass clarinet) was built by Leblanc in 1939.[109] [107] |

See also [edit]

- Listing of clarinet concerti

- List of clarinetists

- List of clarinet makers

- Double clarinet

- International Clarinet Association

References [edit]

Citations [edit]

- ^ Pickett, Joseph, ed. (2018). "clarinet". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (Fifth ed.). Houghton Mifflin. ISBN978-1-328-84169-eight.

- ^ Harper, Douglas (2017). "clarinet". Online Etymology Dictionary . Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- ^ Cresswell, Julia, ed. (2021). "clarinet". Oxford Dictionary of Word Origins (Third ed.). Oxford University Printing. ISBN978-0-1988-6875-0.

- ^ a b c d e f yard h i j k l m north o Page, Janet K.; Gourlay, M. A.; Cringe, Roger; Shackleton, Nicholas; Rice, Albert (2015). "Clarinet". The Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments (Second ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0-1997-4340-7.

- ^ Hoeprich 2008, p. 21.

- ^ Rendall 1971, pp. ane–two, 69.

- ^ Jacobs, Arthur (2017). "clarionet". A New Dictionary of Music. Taylor & Francis. p. 74. ISBN978-1-351-53488-8.

- ^ a b Ellsworth 2015, p. 28.

- ^ Pino 1998, pp. 26–28.

- ^ Black & Gerou 2005, p. 66.

- ^ Black & Gerou 2005, p. 50.

- ^ Reed, Alfred (September 1961). "The composer and the higher ring". Music Educators Journal. 48 (1): 51–53. doi:10.2307/3389717. JSTOR 3389717.

- ^ Cockshott, Gerald; D. 1000. Dent; Morrison C. Boyd; E. J. Moeran (Oct 1941). "English composer goes due west". The Musical Times. 82 (1184): 376–378. doi:ten.2307/922164. JSTOR 922164.

- ^ Hoeprich 2008, p. 278.

- ^ Hoeprich 2008, p. 279.

- ^ a b c d eastward f chiliad h i j Shackleton 1995.

- ^ Lowry 1985, p. 29.

- ^ "Upper altissimo register - Alternating fingering chart for Boehm-system clarinet". The Woodwind Fingering Guide. Archived from the original on 18 November 2016. Retrieved xix November 2016.

- ^ a b c Pino 1998, p. 29.

- ^ Pino 1998, p. 200.

- ^ Miller 2015, p. 176.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j g l "Acoustics of the clarinet". University of New Due south Wales. Archived from the original on 19 Feb 2011. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- ^ a b "Open up vs closed pipes (flutes vs clarinets)". Academy of New South Wales. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- ^ Harris 1995b.

- ^ Backus, J (1961). "Vibrations of the reed and the air column in the clarinet". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 33 (half dozen): 806–809. doi:10.1121/one.1908803.

- ^ Barthet, M.; Guillemain, P.; Kronland-Martinet, R.; Ystad, Due south. (2010). "From clarinet command to timbre perception". Acta Acustica United with Acustica. 96 (four): 678–689. doi:ten.3813/AAA.918322.

- ^ a b Pino 1998, p. 24.

- ^ Gibson, Lee (1968). "Fundamentals of acoustical blueprint of the soprano clarinet". Music Educators Journal. 54 (6): 113–115. doi:10.2307/3391282. JSTOR 3391282.

- ^ Almeida, A; Lemare, J; Sheahan, Yard; Judge, J; Auvray, R; Dang, G; Wolfe, J (2010). Clarinet parameter cartography: automated mapping of the sound produced as a role of bravado pressure level and reed force (PDF). International Symposium on Music Acoustics.

- ^ Pàmies-Vilà, Montserrat; Hofmann, Alex; Chatziioannou, Vasileios (2020). "The influence of the vocal tract on the attack transients in clarinet playing". Journal of New Music Research. 49 (2): 126–135. doi:10.1080/09298215.2019.1708412. PMC7077444. PMID 32256677.

- ^ Blum, David (sixteen August 1992). "Educational activity the clarinet to speak with his voice". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Heaton 1995.

- ^ a b c Zakian, Lee. "The clarinet history". JL Publishing. Archived from the original on 14 Apr 2016. Retrieved ii July 2009.

- ^ Richards, Eastward. Michael. "Single sounds". The Clarinet of the Twenty-Commencement Century. Archived from the original on 11 December 2012. Retrieved ix October 2012.

- ^ Hoeprich 2008, pp. 4, 65, 293.

- ^ a b Hoeprich 2008, p. 4.

- ^ Jenkins, Martin; Oldfield, Sara; Aylett, Tiffany (2002). International Merchandise in African Blackwood (Report). Brute & Flora International. p. 21. ISBNone-903703-05-0.

- ^ Coppenbarger 2015, p. xx.

- ^ Ellsworth 2015, p. 5.

- ^ Saunders, Scott J. (1 January 1952). "Music-making plastics". Music Journal. x (ane): 22–23, 48–51. ProQuest 1290821116 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Ellsworth 2015, p. 94.

- ^ Hoeprich 2008, p. 368.

- ^ Ellsworth 2015, p. 7.

- ^ Hoeprich 2008, pp. 293–294.

- ^ Harris 1995a, p. 74.

- ^ Pino 1998, p. x.

- ^ Pino 1998, p. 21.

- ^ Pine 1998, p. 154.

- ^ Obataya E; Norimoto M. (August 1999). "Audio-visual backdrop of a reed (Arundo donax L.) used for the vibrating plate of a clarinet". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 106 (2): 1106–1110. doi:x.1121/one.427118. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- ^ Lowry 1985, p. 30.

- ^ Pino 1998, p. 19.

- ^ Intravaia, Lawrence J; Robert S. Resnick (Leap 1968). "A research study of a technique for adjusting clarinet reeds". Journal of Research in Music Education. xvi (1): 45–58. doi:ten.2307/3344436. JSTOR 3344436.

- ^ Pino 1998, pp. 153–156.

- ^ Pino 1998, pp. 21, 54–59.

- ^ Pine 1998, p. 38.

- ^ Pino 1998, pp. 39–41.

- ^ a b c d Dobrée 1995.

- ^ a b c Ridley, E.A.Yard. (September 1986). "Birth of the 'Böhm' clarinet". The Galpin Guild Periodical. 39: 68–76. doi:10.2307/842134. JSTOR 842134.

- ^ Pinksterboer 2001, pp. 5–half dozen.

- ^ Horvath, Janet (September 2001). "An orchestra musician'due south perspective on 20 years of performing arts medicine". Medical Issues of Performing Artists. sixteen (3): 102. doi:ten.21091/mppa.2001.3018.

- ^ Corley, Paula (June 2020). "Not similar the others: playing strategies for A, Due east-apartment and bass clarinet". The Clarinet. 47 (iii). Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ Lawson 1995a.

- ^ a b c Karp, Cary (1986). "The early history of the clarinet and chalumeau". Early Music. 14 (4): 545–551. doi:x.1093/earlyj/14.4.545.

- ^ Hoeprich, T Eric (1981). "A 3-central clarinet past J.C. Denner" (PDF). The Galpin Social club Periodical. 34: 21–32. doi:10.2307/841468. JSTOR 841468.

- ^ Pino 1998, pp. 198–199.

- ^ Lawson, Colin (2015). "Chalumeau". The Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments (Second ed.). ISBN9780199743407.

- ^ Hacker, Alan (April 1969). "Mozart and the basset clarinet". The Musical Times. 110 (1514): 359–362. doi:10.2307/951470. JSTOR 951470.

- ^ Pino 1998, p. 204.

- ^ a b c Bray, Erin (xvi November 2004). "The clarinet history". The Clarinet Family unit. Archived from the original on 2 February 2003. Retrieved xx July 2009.

- ^ Pine 1998, p. 212.

- ^ a b c d due east f 1000 Brown 1995.

- ^ Ellsworth 2015, p. 68.

- ^ Benade, Arthur H.; Keefe, Douglas H. (March 1996). "The physics of a new clarinet design". The Galpin Society Journal. 49: 113–142. doi:10.2307/842396. JSTOR 842396.

- ^ Hoeprich 2008, p. 5.

- ^ a b c Longyear, RM (1983). "Clarinet sonorities in early Romantic music" (PDF). The Musical Times. 124 (1682): 224–226. doi:10.2307/962035. JSTOR 962035.

- ^ a b c Lawson 1995c.

- ^ a b c Lawson 1995b.

- ^ a b c d Tschaikov 1995.

- ^ a b c d Harris 1995a.

- ^ a b Miller 2015, p. 385.

- ^ a b Rees-Davies 1995.

- ^ Tuthill, Burnet C. (1972). "Sonatas for clarinet and piano: annotated listings". Journal of Research in Music Education. twenty (3): 308–328. doi:10.2307/3343885. JSTOR 3343885.

- ^ Weerts, Richard M. (Autumn 1964). "The clarinet choir". Journal of Research in Music Education. 12 (3): 227–230. doi:10.2307/3343790. JSTOR 3343790.

- ^ Street, Oscar West. (1915). "The clarinet and its music". Journal of the Majestic Musical Association. 42 (ane): 89–115. doi:10.1093/jrma/42.i.89.

- ^ Kennedy, Joyce; Kennedy, Michael; Rutherford-Johnson, Tim, eds. (2013). "Current of air quintet". The Oxford Dictionary of Music (Sixth ed.). ISBN978-0-1917-4451-8.

- ^ Weerts, Richard K. (Autumn 1964). "The clarinet choir". Journal of Research in Music Didactics. 12 (three): 227–230. doi:10.2307/3343790. JSTOR 3343790.

- ^ Seay, Albert E. (September–October 1948). "Mod composers and the wind ensemble". Music Educators Journal. 35 (1): 27–28. doi:10.2307/3386973. JSTOR 3386973.

- ^ a b Pino 1998, p. 222.

- ^ Suhor 2001, p. 150.

- ^ Palmer, Robert (5 July 1981). "John Carter's instance for the clarinet". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 30 September 2009. Retrieved 1 Apr 2010.

- ^ Bass, Dale (3 August 2018). "Founding the Family Stone". Kamloops This Week . Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- ^ Reeks, John (June 2018). "Rock 'n' roll clarinets?! The Beatles' use of clarinets on Sgt. Pepper'southward Lonely Hearts Club Band". The Clarinet. 45 (three). Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- ^ Farrell, David (31 March 1979). "Closeup: Supertramp—Breakfast In America" (PDF). Billboard. p. 166.

- ^ Slobin, Mark (1984). "Klezmer music: an American ethnic genre". Yearbook for Traditional Music. 16: 34–41. doi:x.2307/768201. JSTOR 768201.

- ^ Shahriari 2015, p. 89.

- ^ Brandl, Rudolf. "The 'Yiftoi' and the music of Greece: office and function". The World of Music. 38 (1): 7–32. JSTOR 41699070.

- ^ Rowlett, Michael (2001). The clarinet in Bulgarian wedding music: An investigation of the relationship between musical style and concepts of ethnicity (DMus dissertation). Florida Land Academy. OCLC 48891055.

- ^ Estrin, Mitchell. "The Turkish clarinet". Dansr . Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- ^ Pino 1998, p. 218.

- ^ Ammer 2004, p. 79.

- ^ Shackleton, Nicholas; Rice, Albert. "Basset clarinet". The Grove Lexicon of Musical Instruments (Second ed.). ISBN9780199743407.

- ^ Baines 1991, p. 129.

- ^ a b Pino 1998, p. 219.

- ^ Shackleton, Nicholas; Rice, Albert. "Alto clarinet". The Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments (Second ed.). ISBN9780199743407.

- ^ Rice 2009, p. 84.

- ^ Shackleton, Nicholas; Rice, Albert. "Bass clarinet". The Grove Lexicon of Musical Instruments (2d ed.). ISBN978-0-1997-4340-7.

- ^ a b Baines 1991, p. 131.

- ^ Mikko, Raasakka (2010). Exploring the Clarinet: A Guide to Clarinet Technique and Finnish Clarinet Music. Fennica Gehrman. p. 82. ISBN978-952-5489-09-5.

- ^ Ellsworth 2015, p. 79.

Cited sources [edit]

- Ammer, Christine (2004). Dictionary of Music (Fourth ed.). Facts on File. ISBN978-ane-4381-3009-5.

- Baines, Anthony (1991). Woodwind Instruments and Their History . Dover Books. ISBN978-0-486268-85-nine.

- Black, Dave; Gerou, Tom (2005). Essential Dictionary of Orchestration. Alfred Music. ISBN978-1-4574-1299-eight.

- Coppenbarger, Brent (2015). Fine-Tuning the Clarinet Department: A Handbook for the Band Managing director. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN9781475820775.

- Ellsworth, Jane (2015). A Dictionary for the Modern Clarinetist. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN978-0-8108-8648-iii.

- Hoeprich, Eric (2008). The Clarinet. Yale University Press. ISBN978-0-300-10282-half-dozen.

- Lawson, Colin, ed. (1995). The Cambridge Companion to the Clarinet . Cambridge University Press. ISBN978-0-521-47668-3.

- Lawson, Colin (1995a). "Unmarried reeds before 1750". In Lawson, Colin (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Clarinet . Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–15. ISBN978-0-521-47668-iii.

- Shackleton, Nicholas (1995). "The development of the clarinet". In Lawson, Colin (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Clarinet . Cambridge University Press. pp. 16–32. ISBN978-0-521-47668-3.

- Lawson, Colin (1995b). "The clarinet family". In Lawson, Colin (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Clarinet . Cambridge University Press. pp. 33–37. ISBN978-0-521-47668-3.

- Lawson, Colin (1995c). "The C clarinet". In Lawson, Colin (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Clarinet . Cambridge University Press. pp. 38–42. ISBN978-0-521-47668-3.

- Tschaikov, Basil (1995). "The loftier clarinets". In Lawson, Colin (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Clarinet . Cambridge University Press. pp. 43–56. ISBN978-0-521-47668-3.

- Dobrée, Georgina (1995). "The basset horn". In Lawson, Colin (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Clarinet . Cambridge University Press. pp. 57–65. ISBN978-0-521-47668-3.

- Harris, Michael (1995a). "The bass clarinet". In Lawson, Colin (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Clarinet . Cambridge University Printing. pp. 66–74. ISBN978-0-521-47668-three.

- Rees-Davies, Jo (1995). "The development of the clarinet repertoire". In Lawson, Colin (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Clarinet . Cambridge Academy Press. pp. 75–91. ISBN978-0-521-47668-three.

- Harris, Paul (1995b). "Teaching the clarinet". In Lawson, Colin (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Clarinet . Cambridge Academy Press. pp. 123–133. ISBN978-0-521-47668-3.

- Heaton, Roger (1995). "The contemporary clarinet". In Lawson, Colin (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Clarinet . Cambridge University Press. pp. 163–183. ISBN978-0-521-47668-3.

- Chocolate-brown, John Robert (1995). "The clarinet in jazz". In Lawson, Colin (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Clarinet . Cambridge University Press. pp. 184–198. ISBN978-0-521-47668-3.

- Lowry, Robert (1985). Practical Hints on Playing the B-Apartment Clarinet. Alfred Publishing. ISBN978-0-7692-2409-1.

- Miller, RJ (2015). Contemporary Orchestration. Routledge. ISBN978-1-3178-0625-7.

- Pinksterboer, Hugo (2001). Tipbook: Clarinet. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN978-90-761-9246-8.

- Pine, David (1998). The Clarinet and Clarinet Playing . Dover Books. ISBN978-0-486-40270-3.

- Rendall, Geoffrey F. (1971). The Clarinet: Some Notes Upon Its History and Construction (3rd ed.). Westward. Due west. Norton & Company Inc. ISBN978-0-393-02164-6.

- Rice, Albert R. (2009). From the Clarinet D'Amour to the Contra Bass: A History of Large Size Clarinets, 1740–1860. Oxford University Printing. ISBN978-0-xix-971117-8.

- Shahriari, Andrew (2015). Popular World Music. Routledge. ISBN978-1-3173-4538-1.

- Suhor, Charles (2001). Jazz in New Orleans: The Postwar Years Through 1970. Scarecrow Press. ISBN978-1-4616-6002-6.

Further reading [edit]

- Bessaraboff, Nicholas (1941). Ancient European Musical Instruments. Harvard University Press.

- Brymer, Jack. Clarinet. Yehudi Menuhin Music Guides. Kahn & Averill. ISBN978-0-3560-8414-5.

External links [edit]

- The International Clarinet Association

- Clarinet at Curlie

Highest Note On A Clarinet,

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clarinet

Posted by: gentrysaughts1992.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Highest Note On A Clarinet"

Post a Comment